3.1.6. Wen (2012) “Wet/Dry Areas Method”¶

Wen, X. “Wet-dry areas method for interfacial (free surface) flow”, International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids, vol 71, pp 316 - 338, 2012

3.1.6.1. Where is this study placed within the wave modelling community?¶

3.1.6.1.1. Non-linear Breaking Waves in Shallow Water¶

This paper has an important application to non-linear breaking waves in shallow water. The approach taken in this category follows the fully non-linear equations for a deterministic time-resolving model for one realisation of wave frequency, similar to the approach of Ravel et al (2009). However, unlike Ravel, the numerical method used reformulates the convective mass fluxes in order to allow highly non-linear behaviour at the interface. This allows breaking waves to be considered, which was not considered by Ravel et al (2009).

It is known in the wave modelling community that as the water depth reduces, wave breaking becomes an important phenomenon. However, there is also the simultaneous effect of bottom friction, and it is difficult to separate the effect of bottom friction from the effect of wave breaking in shallow water. Although this study focusses mainly on wave breaking, it follows the approach outlined by Cavaleri et al (2007) in which wave breaking and bottom friction could be studied together if needed.

The time resolving approach may be better suited to non-linear breaking in shallow water compared with stochastic methods because of the highly non-linear and dissipative effects that are present. However, there is an inherent computational penalty of the time-resolving approach as multiple realisations may be needed.

3.1.6.1.2. Numerics¶

This study is also in the class of numerics, attempting to minimise the numerical errors created due to the description of the flow field.

The approach has the potential to introduce less numerical error compared to the arithmetic mean approach for the density term in the convective mass fluxes of say Zwart, Burns and Galpin (2007).

The approach is 2D, such that the wet-dry areas are really wet-dry lengths, but most numerical simulations of this type are 2D.

3.1.6.2. Summary of Findings¶

New numerical method for 2D free surface flows using:

Standard staggered grid

Conservative integral form of Navier-Stokes equations

2 continuity equations: 1) mass conservation, 2) volume conservation

Convective mass flux computed from wet/dry area exposed

Main benefit compared to standard approaches:

The mean density approach can be shown to produce 450 times the convective mass flux compared with the wet-dry areas method.

The mean viscosity approach produces 10 times the diffusive mass flux, due to the smaller change in viscosity compared to density across the interface (so this was not considered).

Comparison between this new method shows good agreement with:

Analytical solution

Experimental images

Experimental velocities

3.1.6.3. Literature Review¶

3.1.6.3.1. Problems¶

Instantaneous density jump across a free surface - use conservative integral form of Navier-Stokes because density in convection term stays inside integrand

Computing accurate velocity field, hence shear stress for wind blowing over waves - use finite volume method to ensure conservation of mass and momentum

3.1.6.3.2. Purposes¶

Purpose 1: Explore conservative integral form for free surface flows

The conservative integral form of the Navier-Stokes equations has been used in the cut-cell method - to cut solid boundaries from the Cartesian grid to include only fluid in the calculation

High resolution Godunov scheme was used for free surface flows to calculate density and velocity

Cut cell method has been used to cut air out of the solution

Purpose 2: Accurately calculate mass fluxes using standard staggered grid

Mass fluxes passing through the u and v control volumes are the most important

For co-located grids, mass fluxes on the f control volumes have been for the mass fluxes on the u and v control volumes before

For staggered grids, more difficult to get u and v fluxes from f flux - can use an f-grid that is twice as fine as the u and v grid - but this is not standard

Other features

Second order scheme for time derivatives

High-resolution scheme for interpolation of velocity onto the surface of the control volume

Second order scheme for viscous terms

SIMPLEC-PISO scheme for pressure-velocity coupling

Explicit high resolution compressive interface capturing scheme for arbitrary meshes (CICSAM) for predicting the volume fraction of the fluid

3.1.6.4. Mathematical Formulation¶

3.1.6.4.1. Governing Equations¶

Volume Conservation:

Mass Conservation:

Momentum Conservation for \(u\):

Momentum Conservation for \(v\):

Volume Fraction Conservation:

where:

\(\mathbf n = n_x \mathbf i + n_y \mathbf j = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \text{for east surface}, \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \text{for north surface}, \begin{bmatrix} -1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \text{for west surface}, \begin{bmatrix} 0 & -1 \end{bmatrix} \text{for south surface}\)

\(\mathbf v = u \mathbf i + v \mathbf j\) = \(\begin{bmatrix} u \\ v \end{bmatrix}\)

\(n_x = 1 \text{ for east surface}, -1 \text{ for west surface}\), \(n_y = 1 \text{ for north surface}, -1 \text{ for south surface}\)

\({\partial \over \partial n} = {\partial \over \partial x} \text{ for east surface}, -{\partial \over \partial x} \text{ for west surface}\), \({\partial \over \partial y} \text{ for north surface}, -{\partial \over \partial y} \text{ for south surface}\)

Unknowns:

Velocities \(u\) and \(v\)

Pressure \(p\)

Volume fraction \(f\)

3.1.6.4.2. Discretisation of Governing Equations¶

Aim: Obtain an algebraic formulation for velocities at centre of control volume \(u_P\) and \(v_P\)

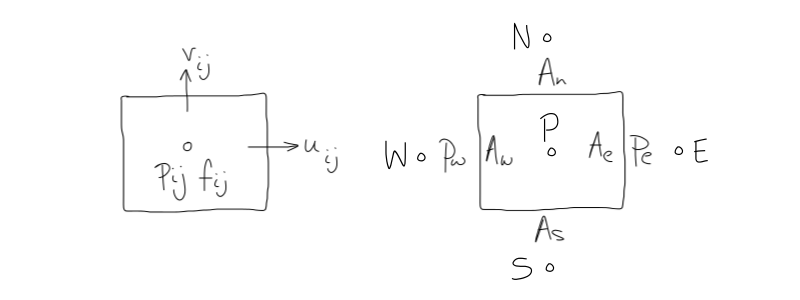

LHS: Staggered Location for \(u, v, p\) and \(f\) RHS: \(u\) control volume

Discrete Mass Conservation Equation

Mass Conservation Equation (2) - all values are at time n+1

Discrete Momentum Conservation Equation for \(u\)

Momentum Conservation Equation (3) - all values are at time n+1

3.1.6.4.3. Apply Numerical Schemes¶

3.1.6.4.3.1. Transient Terms: Second Order Backward Euler¶

Simplification to 1st Order (to illutrate numerical scheme): all values are at n+1 unless stated otherwise (including the derivative)

3.1.6.4.3.2. Velocity Terms at Faces: Blended Scheme¶

where for flow in +ve x-direction: \(\beta = 0 \text{ (1st order upwind)}\) \(\beta = {{u_E-u_P} \over {u_P-u_W}} \text{ (central)}\) and \(\beta = 1 \text{ (2nd order upwind)}\)

For flow in other directions:

Face velocity |

+ve upwind |

-ve upwind |

Central |

+ve 2nd order upwind |

-ve 2nd order upwind |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

\(u_e\) |

\(u_P\) |

\(u_E\) |

\({u_P+u_E} \over 2\) |

\({3u_P-u_W} \over 2\) |

\({3u_E-u_{EE}} \over 2\) |

\(u_w\) |

\(u_W\) |

\(u_P\) |

\({u_W+u_P} \over 2\) |

\({3u_W-u_{WW}} \over 2\) |

\({3u_P-u_E} \over 2\) |

\(u_n\) |

\(u_P\) |

\(u_N\) |

\({u_P+u_N} \over 2\) |

\({3u_P-u_S} \over 2\) |

\({3u_N-u_{NN}} \over 2\) |

\(u_s\) |

\(u_S\) |

\(u_P\) |

\({u_S+u_P} \over 2\) |

\({3u_S-u_{SS}} \over 2\) |

\({3u_P-u_N} \over 2\) |

Simplification to 1st order upwind scheme (to illustrate numerical scheme)

\(F_e > 0 \Rightarrow u_e = u_P\)

\(F_e < 0 \Rightarrow u_e = u_E\)

where \(\begin{bmatrix} F_e, & 0 \end{bmatrix}\) means the maximum of \(F_e\) and 0

Similarly:

3.1.6.4.3.3. Apply the First Order Schemes to the Momentum and Continuity Equations¶

Rule: With no source terms, and in steady flow, when all the values of \(u\) are the same at the edges, the central value of \(u\) must be equal to them. This means we must take \(u_P\) times the continuity equation away from the momentum equation

Momentum Equation (7) - \(u_P\) times Continuity Equation (6)

Apply the identities:

\(\begin{bmatrix}F_e, & 0 \end{bmatrix} - F_e = \begin{bmatrix}-F_e, & 0 \end{bmatrix}\)

\(\begin{bmatrix}-F_w, & 0 \end{bmatrix} + F_w = \begin{bmatrix}F_w, & 0 \end{bmatrix}\)

\(\begin{bmatrix}F_n, & 0 \end{bmatrix} - F_n = \begin{bmatrix}-F_n, & 0 \end{bmatrix}\)

\(\begin{bmatrix}-F_s, & 0 \end{bmatrix} + F_s = \begin{bmatrix}F_s, & 0 \end{bmatrix}\)

Collect like terms: higher order terms (h.o.t) would be collected on the R.H.S. (all values at n+1 unless otherwise stated):

Similarly for the \(v\) momentum equation and continuity equation (all values at n+1 unless otherwise stated):

Note: The Rule we needed in steady state with no source terms holds, since \(a_P = a_E + a_W + a_N + a_S\)

Such that in this situation \(u_P = u_E = u_W = u_N = u_S\)

The wet-dry areas method must now DESCRIBE the following for u-control volume and v-control volume:

Convective fluxes \(F_e, F_w, F_n, F_s\) (using new method for wet-dry lengths at each face)

Diffusive fluxes \(D_e, D_w, D_n, D_s\) (using conventional harmonic mean viscosity approach)

Mass of control volume \(m_P\) (using conventional arithmetic mean density approach)

3.1.6.5. The Wet-Dry Areas Method¶

Terms integrated over the surface:

Volume flux \(m^3s^{-1}m^{-2}\) (in the Volume Conservation Equation (1) and Volume Fraction Conservation Equation (5))

Mass flux \(kgs^{-1}m^{-2}\) (in the Mass Conservation Equation (2))

Convective acceleration (in the u Momentum Equation (3) and the v Momentum Equation (4))

Diffusion (in the u Momentum Equation (3) and the v Momentum Equation (4))

Terms integrated over the volume:

Unsteady acceleration (in the Mass Conservation Equation (2), u Momentum Equation (3), v Momentum Equation (4) and Volume Fraction Conservation Equation (5))

Body forces (in the v Momentum Equation (4))

3.1.6.5.1. u-control volume¶

Determine the Flux Terms by considering the Convective Term for the North Face:

Similarly:

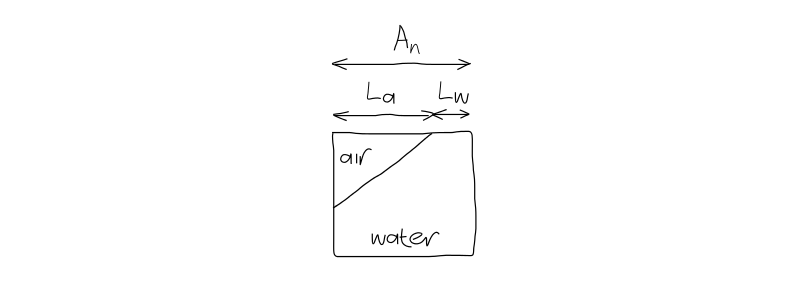

What value do the terms \(L_a\) and \(L_w\) have?

State |

\(L_a\) |

\(L_w\) |

|---|---|---|

100% air |

\(\Delta x\) |

0 |

100% water |

0 |

\(\Delta x\) |

air-water mix |

\(\Delta x - L_w\) |

\(\Delta x - L_a\) |

Outward Normal Vector

Negative sign indicates that the change in volume fraction in the positive x and y directions is negative

Case 1: \(-{{\partial f} \over {\partial y}}>0\) and \(\left\vert{{\partial f} \over {\partial y}}\right\vert>\left\vert{{\partial f} \over {\partial x}}\right\vert\)

Case 2: \(-{{\partial f} \over {\partial y}}<0\) and \(\left\vert{{\partial f} \over {\partial y}}\right\vert>\left\vert{{\partial f} \over {\partial x}}\right\vert\)

Case 3: \(-{{\partial f} \over {\partial x}}>0\) and \(\left\vert{{\partial f} \over {\partial x}}\right\vert>\left\vert{{\partial f} \over {\partial y}}\right\vert\)

Case 4: \(-{{\partial f} \over {\partial x}}<0\) and \(\left\vert{{\partial f} \over {\partial x}}\right\vert>\left\vert{{\partial f} \over {\partial y}}\right\vert\)

Now we only need to calculate the wet dry areas case 1, and then rotate it’s orientation for the other cases.

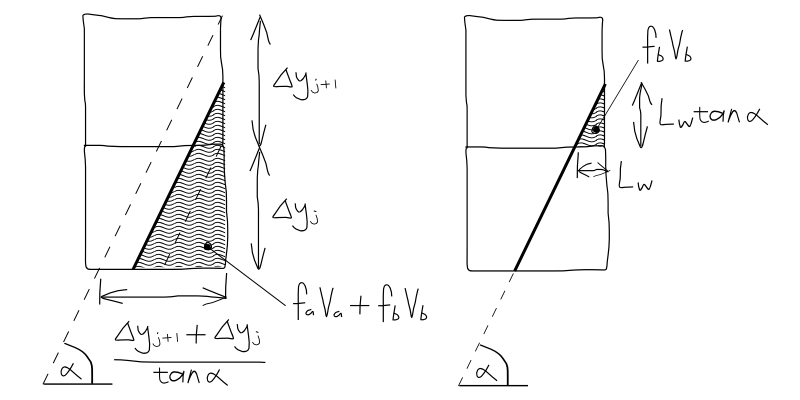

3.1.6.5.1.1. \(L_w\) and \(L_a\) where \(tan(\alpha) < \Delta y / \Delta x\) on north face¶

Consider Case 1

Compute for each u and v control volume:

Wet area

Dry area

Viscosity on each face

Total mass

Assumptions:

Angle between unit vector \(\mathbf n\) and positive y axis is in the range -45 degrees to +45 degrees

Bottom to top, \(f\) and \(\mu\) are discontinuous

Left to right, the \(f\) is a continous function and conventional interpolation or averaging can be applied

Air-water interface is a straight line in control volume

A table might also clarify:

Case |

\(f_{i,j}\) |

\(f_{i+1,j}\) |

\(f_{i,j+1}\) |

\(f_{i+1,j+1}\) |

\(tan(\alpha)\) |

\(\alpha\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

1 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0 |

\(\left \vert 1 \right \vert\) |

45 |

2 |

0 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

1 |

\(\left \vert 1 \right \vert\) |

45 |

1 flipped horizontally |

0.5 |

1 |

0 |

0.5 |

\(\left \vert -1 \right \vert\) |

45 |

2 flipped horizontally |

0.5 |

0 |

1 |

0.5 |

\(\left \vert -1 \right \vert\) |

45 |

The volume fraction is continuous from left to right, so the standard average process is applied:

\(f\) is defined as:

\(1-f\) is defined as:

For similar triangles:

Hence:

Solution for \(L_w\)

Solution for \(L_a\)

If \(f_b = 0\) and \(f_a = 1\) then \(L_w = 0\) and \(L_a = \Delta x\)

If \(f_b = 1\) and \(f_a = 0\) then \(L_w = \Delta x\) and \(L_a = 0\)

Advantages of Equation (22):

We don’t need to know that the interface is between P and N for Equation (22)

We don’t need the angle \(\alpha\)

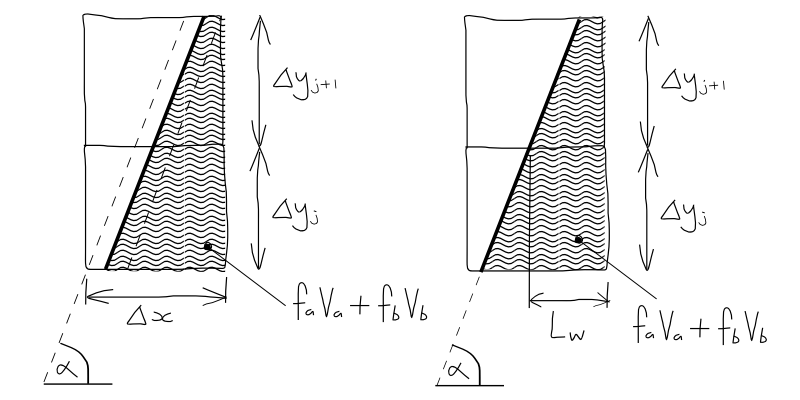

3.1.6.5.1.2. \(L_w\) and \(L_a\) where \(tan(\alpha) > \Delta y / \Delta x\) on north face¶

Case A solution for \(L_w\) ( \(L_a\) from equation (23) )

Case B solution for \(L_w\) ( \(L_a\) from equation (23) )

Area of a triangle:

Case C solution for \(L_w\) ( \(L_a\) from equation (23) )

From the area of a trapezoid:

Case D solution for \(L_w\) (this is just Case B but rotated 180 degrees and i.t.o. air \(L_a\) from equation (23) )

From Case B (i.t.o. air):

From the area of a triangle:

Case E solution for \(L_w\) (this is just Case A but rotated 180 degrees and i.t.o. air \(L_a\) from equation (23) )

From Case A (i.t.o. air):

From the area of a triangle:

3.1.6.5.1.3. \(L_w\) and \(L_a\) on south, east and west faces¶

Solution for \(L_w\) on south face by replacing \(j\) by \(j-1\) in equations (20), (21), (22), (23), (24), (25), (26), (27), (28)

Solution for \(L_w\) on east face:

Solution for \(L_w\) on west face by replacing \(i\) by \(i-1\) in (29)

Solution for \(L_a\) on south face from equation (23)

Solution for \(L_a\) on west and east face

3.1.6.5.1.4. \(\mu\) on north face (\(\mu_n\))¶

What do we need to compute?

The diffusive flux on the north face:

What is \(\mu_n\)?

We are concerned with the viscosity at the interface between points P and N.

As Patankar (1980) suggests, we must determine the distance to the interface from the points P and N.

The governing assumption here is that very steep angles > 45 degrees or < -45 degrees are not present

Note that this assumption only applies to the viscosity and not to the convective flux, which does allow sharp angles

The second governing assumption is that the viscosity at the interface is represented by the harmonic mean, so significant variation in the viscosity (e.g. due to turbulence) between the grid points at the interface is negligible

The use of the harmonic mean follows the suggestion of Patankar (1980) who used it for non-uniform conductivity in the diffusive term. Patankar (1980) dismisses the use of the arithmetic mean as too simplistic, but he did not consider the geometric mean or the infinite norm mean see Schmeling et al (2008). We also don’t know whether turbulent viscosity can be best represented by these averaging methods.

There are four cases:

\(f_a < 0.5\) and \(f_b = 0\) so \(d_w = 0\)

\(f_a > 0.5\) and \(f_b = 0\) so \(d_w = (f_a - 0.5)\Delta y_j\)

\(f_a > 0.5\) and \(f_b < 0.5\) so \(d_w = {(f_a - 0.5)\Delta y_j} +f_b \Delta y_{j+1}\)

\(f_a > 0.5\) and \(f_b > 0.5\) so \(d_w = {(f_a - 0.5)\Delta y_j} +0.5 \Delta y_{j+1}\)

This can be summarized like this, where \(d_w\) is the distance from P to the interface:

The distance from N to the interface is \(d_a\) and this is simply the distance between P and N minus \(d_w\):

Harmonic Mean Viscosity

This is how Patankar (1980) defines the harmonic mean viscosity (for the north face):

Where:

And:

Substituting Equation (33) and (34) into (32) and re-arranging gives:

3.1.6.5.1.5. \(\mu\) on the south, east and west faces (\(\mu_s\), \(\mu_e\), \(\mu_w\))¶

Solution for \(\mu_s\) on south face by replacing \(j\) by \(j-1\) in equation (30) and (31)

Solution for \(\mu_e\) on east face by convectional VOF method (the arithmetic mean) assuming linear variations in viscosity:

Solution for \(\mu_w\) on west face by replacing \(i\) by \(i-1\) in equation (36)

3.1.6.5.1.6. Total mass in u-control volume¶

The total mass in the u-control volume can be seen as a function of time, because the values of \(f\) are changing with time, especially near the interface. So the mass in the control volume is:

(Seriously consider changing \(f_a\) to \(f_P\) and \(f_b\) to \(f_N\) to avoid confusion with air)

3.1.6.5.2. v-control volume¶

The angle \(\alpha\) is from Brackbill et al (1994) - I’m not sure why the angle the interface makes with the x-axis would be different for the v control volume? Or why we would need another equation for the same value? Is this because the v-volume fraction is stored at the faces and not the cell centres?

Why isn’t this the same as Equation (19)?

3.1.6.5.2.1. \(L_w\) and \(L_a\) where \(tan(\alpha) < \Delta y / \Delta x\) on north face¶

Case A - Solution for \(L_w\)

Case B - Solution for \(L_w\)

From the area of a trapezoid:

Case C - Solution for \(L_w\)

3.1.6.5.2.2. \(L_w\) and \(L_a\) where \(tan(\alpha) > \Delta y / \Delta x\) on north face¶

Case A - Solution for \(L_w\)

Case B - Solution for \(L_w\)

From the area of a triangle:

Case C - Solution for \(L_w\)

Case D - Solution for \(L_w\)

Case E - Solution for \(L_w\)

Resulting flux

Depending on the value of \(f_{i,j+1}\) and \(\alpha\), the fluid flux produced may vary from:

\(\rho_a v_n \Delta x\) when \(L_w = 0\) and \(L_a = \Delta x\)

\(\rho_w v_n \Delta x\) when \(L_w = \Delta x\) and \(L_a = 0\)

3.1.6.5.2.3. \(L_w\) and \(L_a\) on south, east and west faces¶

Solution for \(L_w\) on south face by replacing \(j\) by \(j-1\) in equations for north face

Solution for \(L_w\) on east face

not sure about the following:

Solution for \(L_w\) on west face by replacing \(i-1\) with \(i\) in equations for east face

3.1.6.5.2.4. \(\mu\) on north face (\(\mu_n\))¶

I’m not sure about the positioning of the indices, in the above equations

BIG QUESTION: Why is the wet length based on the u-volume fraction cell-centred and the wet length based on the v-volume fraction face-centred?

The harmonic mean is used for the viscosity \(\mu_n\) from Equation (35)

3.1.6.5.2.5. \(\mu\) on the south, east and west faces (\(\mu_s\), \(\mu_e\), \(\mu_w\))¶

Solution for \(\mu_s\) on south face by replacing \(j+1\) by \(j\) in equation (37) and (38)

Solution for \(\mu_e\) on east face by convectional VOF method (the arithmetic mean) assuming linear variations in viscosity:

Similar to \(L_w\):

Solution for \(\mu_w\) on west face by replacing \(i\) by \(i-1\) in equations for east face

3.1.6.5.2.6. Total mass in v-control volume¶

The total mass in the v-control volume:

Similar to \(L_w\):

It should be mentioned that there are various methods for reconstructing the interface, e.g. Rider and Kothe (1998)

3.1.6.6. Solution Algorithms¶

3.1.6.6.1. SIMPLE and SIMPLEC Algorithms¶

The u momentum equation (17) and v momentum equation (18) are solved iteratively until the normalised residuals are small (perhaps using the tri-diagonal matrix algorithm). At this point we have satisfied momentum conservation.

However, there is no guarantee that this solution satisfies the volume conservation equation, from equation (1):

A pressure-correction algorithm is needed in the loop in order to satisfy volume conservation by correcting the following according to the volume conservation equation:

velocity

pressure

3.1.6.6.1.1. SIMPLE¶

The SIMPLE algorithm leads to a slow convergence when there is a sudden change in the geometry or solution property. The u velocity correction is \(u_P^c\):

3.1.6.6.1.2. SIMPLEC¶

The SIMPLEC algorithm is used instead:

Now obtain the pressure correction by replacing \(u = u^* + u^c\) (\(u\) is the true velocity and equals the uncorrected velocity \(u^*\) plus the corrected velocity \(u^c\))

where b is the mass imbalance around P:

The pressure and velocity corrections are applied like this:

3.1.6.6.2. CICSAM Algorithm¶

At this point we have satisfied the equations for volume, mass, u momentum and v momentum conservation.

The final equation to satisfy is the equation for volume fraction conservation (5), which is solved explicitly:

The values on the surfaces are computed by a high resolution scheme CICSAM. The reason for using CICSAM is that this method is able to produce a sharp water surface

Normal to the interface, the volume fraction is between 0 and 1 on only one node.

The problem with Equation (39) is that when the points \(u, w, n, s\) and \(P\) are all in water, the RHS of Equation (39) is:

Clearly \(f_P\) won’t be exactly 1, so the equation for volume fraction conservation won’t reduce to the equation of volume conservation (which it should in this case). So in solving Equation (39) a correction is applied to the velocity:

The correction is applied like this to Equation (39)

3.1.6.6.3. CICSAM, SIMPLE-PISO Procedure¶

In order to accelerate convergence, we add a second velocity and pressure produced by the PISO algorithm at the last iteration in each time step

The implicit SIMPLEC-PISO algorithm is combined with the explicit CICSAM algorithm like this:

The solution of volume fraction is calculated from the solutions of \(u^n\), \(v^n\) and \(f^n\) by CICSAM.

The solutions of \(u\), \(v\) and \(p\) are obtained from the SIMPLEC-PISO algorithm after \(f\) has already been obtained.

3.1.6.7. Application to a Non-Linear, Non-Breaking Deep Water Wave¶

A wave is modelled using the inviscid non-linear solution to the wave equation as the inlet and initial conditions (the harmonic solution to the velocity potential described by Laplace’s equation plus boundary conditions).

The model uses \(h/L = 0.6\) i.e. it’s a deep water case (\(h/L > 0.5\))

Also \(ka = 0.1885\) i.e. it’s non-linear (\(ka > 0.1\))

And \(2a/L = 0.06\) i.e. it’s non-breaking (\(2a/L < 0.08\))

No wind input is used, i.e. the air follows the water

The model has a wall at the bottom boundary, a symmetry condition at the top, an inlet velocity, plus an opening at the outlet.

3.1.6.7.1. Velocity¶

- Potential flow compares well with the wet-dry areas method in the water, however the difference occurs in the air and near the interface:

The velocity field is discontinuous in the potential flow solution, because the viscosity is zero

The wet-dry areas method produces a rapid but continuous change in the velocity field

However remarkably over most of the velocity profile the difference is less than 1%

The v-velocity variation is continuous in both cases and little difference is seen

3.1.6.7.2. Streamlines¶

At the peak and trough, streamlines for potential flow are centred at the interface, whereas streamlines for the wet-dry areas method are centred in the air

Generally speaking this exercise of comparing the potential flow solution with the wet-dry areas method was for validation purposes and it showed that sensible results are being produced

I wonder whether a comparison between the standard arithmetic approach to the mass fluxes and the wet-dry areas method would also be useful to compare the shear stress computed at the interface.

3.1.6.8. Application to Collapse of a Water Column¶

The validation with experimental data was also conducted against images for the a collapse of a water column.

It was found that the qualitative flow features, such as the hump in the water column, the strong jetting and the air pocket near the wall were all present in both the simulation and the experimental images. However, as the paper admits, there is no quantitative measurement to make this validation more complete.

3.1.6.9. Application to a Non-Linear, Breaking Shallow Water Wave¶

The breaking point is defined as the point where the speed of the water particles becomes larger than the phase speed of the wave.

At this point the front of the water wave becomes vertical.

To test whether the physics of this phenomenon is reproduced, a numerical simulation was run with the wet-dry areas method using the same parameters as the PIV experiment of Change and Liu (1998), which is where wave breaking was measured.

Wave steepness: \(2a/L = 0.12\) (i.e. \(2a/L > 0.08\) which implies a breaking wave)

Depth: \(h/L = 0.166\) (i.e. \(h/L < 0.5\) which implies a shallow wave)

It was found that the dimensionless water particle velocity was in the range 1.0c to 1.1c (where c is the phase speed), which matches the measured value of 1.07c.

3.1.6.10. Grid Independence, Robustness and Efficiency of the Wet-Dry Areas Method¶

3.1.6.10.1. Grid Independence¶

This was performed for the water column collapse application for T=3.99.

Uniform, structured grids were used in this case.

I wonder whether non-uniform structured grids or non-uniform unstructured grids might be more numerically efficient, although they may not be less diffuse.

3.1.6.10.2. The Robustness¶

The first 20 timesteps of the water column collapse application was also used test robustness.

The SIMPLEC algorithm used is unconditionally stable, however the convergence at each timestep depends on the timestep - i.e. divergence may occur if the timestep is too large.

The robustness was tested by using a fixed timestep and testing to see if the volume residual became less than \(5x10^{-4}\)

The minimum number of iterations per timestep was set to 15, which was achieved quickly after the first five timesteps.

3.1.6.10.3. Efficiency¶

The efficiency of the wet-dry areas method is less than the average density method due to the use of different cases in the u and v control volumes

For the water column collapse it is 20% greater (as this uses all 4 cases)

For the non-linear non-breaking wave and the non-linear breaking wave it is around 10% longer (as these are mainly case 1)

3.1.6.11. Conclusions¶

The Navier-Stokes Equations have been solved using:

Conservative integral form

Standard staggered grid

A new analytical expression for wet-dry areas in the convective mass flux (instead of the standard average density approach), which is a function of volume fraction

SIMPLEC algorithm (which is faster than SIMPLE for interfacial flows)

Advantages of wet-dry areas method:

Improves the computation of convective mass flux

Bussmann’s consistency problem is avoided

The new numerical method is robust

Disadvantages of wet-dry areas method:

Less efficient than the average density approach.